AI for journalists

These notes are mostly inspired from the Practical AI for (investigative) journalism sessions.

There are many excellent uses for AI in journalism. You can find some of them on the Journalist’s Toolbox website.

However, there is one important thing to keep in mind. AI tools are machines that generate text (or other forms of media), not facts.

Let’s look at an example. I asked Claude to tell me Who is Nicu Calcea?.

Nicu Calcea is a Romanian politician who has served as a member of the European Parliament since 2019. He is a member of the National Liberal Party (PNL) which is a center-right liberal-conservative political party in Romania.

Some key facts about Nicu Calcea: - Born in 1968 in Buzău, Romania - He has a background in economics, having graduated from the Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies - Prior to entering politics, he had a business career in the private sector - He was first elected to the European Parliament in 2019 on the PNL party list - In the European Parliament, he sits with the Renew Europe group, which is liberal and pro-European Union - His main areas of focus are economic and monetary affairs as well as the single market - Within the PNL party in Romania, he is viewed as being part of the liberal/pro-European wing

So in summary, he is a Romanian liberal politician currently serving as an MEP after previously working in the private business sector. His political positions are generally pro-EU and pro-market economics.

Claude seems to be very confident and gives a pretty detailed response. However, every single one of the “key facts” on that list is false. I know, because I am Nicu Calcea, and there is no Romanian politician with the same name.

In the context of Large Language Models (LLMs), these falsehoods are called “hallucinations”.

Why does this happen?

How AI works

Let’s assume I ask you to guess the next word in this sentence: I'm .... The answer could be hungry, Nicu, confused, or anything else.

What about if we say I haven't eaten since yesteday, I'm .... Then, the answer is likely to be hungry or starving.

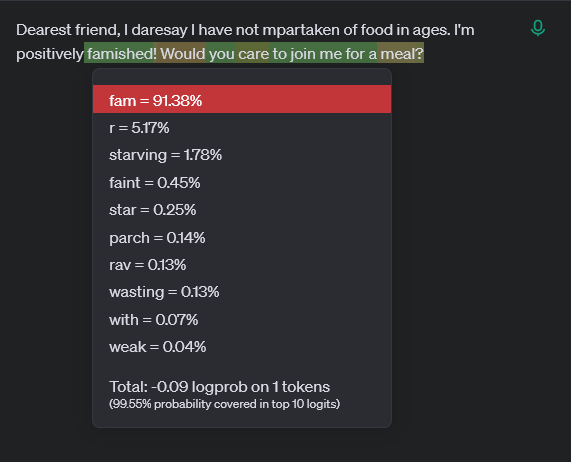

Let’s take yet another example: Dearest friend, I daresay I have not partaken of food in ages. I'm positively.... Based on the style of the sentence, a better fit would be famished.

What we did is we looked at all the words that came before and filled in the most appropriate choice. This is similar to how a Large Language Model (LLM) works.

You can see this in action in the OpenAI Playground. Copy the last sentence in the text box, make sure you have the Show probabilities box ticked on and click Submit to let the LLM complete it.

You’ll notice the completed words have been highlighted in different colours, and clicking on the highlighted blocks will show you several options and percentages. This indicates the most likely next “token”, or group of letters. In our example, there was a 91.38% chance that the sentence Dearest friend, I daresay I have not partaken of food in ages. I'm positively would be followed by fam, which had a 99.87% change of being followed by ished, and so on.

To keep the responses dynamic, LLMs apply a degree of randomness to choosing the next token. This means that asking the same question multiple times may give you different answers.

You can adjust the Temperature slider in the Playground to control that degree of randomness, where a lower number makes the reply more precise and predictable, while the higher one makes it more creative. For journalism, you’ll normally want to set the temperature to 0, as that will return the most likely output, which is likely to be more precise.

In essence, this is a more advanced version of the text predictor on your smartphone. That’s why you can’t trust that its output is the truth, though it often is. It is just the statistically most likely word based on the existing text.

While this is less of an issue for some uses, like creative writing or poetry, journalism is about facts. AI tools are still very bad at reporting.